Transfer prices are almost inevitably needed whenever a business is divided into more than one department or division

In accounting, many amounts can be legitimately calculated in a number of different ways and can be correctly represented by a number of different values. For example, both marginal and total absorption cost can simultaneously give the correct cost of production, but which version of cost you should use depends on what you are trying to do.

Similarly, the basis on which fixed overheads are apportioned and absorbed into production can radically change perceived profitability. The danger is that decisions are often based on accounting figures, and if the figures themselves are somewhat arbitrary, so too will be the decisions based on them. You should, therefore, always be careful when using accounting information, not just because information could have been deliberately manipulated and presented in a way which misleads, but also because the information depends on the assumptions and the methodology used to create it. Transfer pricing provides excellent examples of the coexistence of alternative legitimate views, and illustrates how the use of inappropriate figures can create misconceptions and can lead to wrong decisions.

When transfer prices are needed

Transfer prices are almost inevitably needed whenever a business is divided into more than one department or division. Usually, goods or services will flow between the divisions and each will report its performance separately. The accounting system will usually record goods or services leaving one department and entering the next, and some monetary value must be used to record this. That monetary value is the transfer price. The transfer price negotiated between the divisions, or imposed by head office, can have a profound, but perhaps arbitrary, effect on the reported performance and subsequent decisions made.

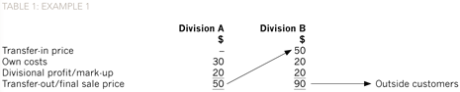

Example 1

Take the following scenario shown in Table 1, in which Division A makes components for a cost of $30, and these are transferred to Division B for $50. Division B buys the components in at $50, incurs own costs of $20, and then sells to outside customers for $90.

As things stand, each division makes a profit of $20/unit, and it should be easy to see that the group will make a profit of $40/unit. You can calculate this either by simply adding the two divisional profits together ($20 + $20 = $40) or subtracting both own costs from final revenue ($90 – $30 – $20 = $40).

You will appreciate that for every $1 increase in the transfer price, Division A will make $1 more profit, and Division B will make $1 less. Mathematically, the group will make the same profit, but these changing profits can result in each division making different decisions, and as a result of those decisions, group profits might be affected.

Consider the knock-on effects that different transfer prices and different profits might have on the divisions:

Performance evaluation. The success of each division, whether measured by return on investment (ROI) or residual income (RI) will be changed. These measures might be interpreted as indicating that a division’s performance was unsatisfactory and could tempt management at head office to close it down.

Performance-related pay. If there is a system of performance-related pay, the remuneration of employees in each division will be affected as profits change. If they feel that their remuneration is affected unfairly, employees’ morale will be damaged.

Make/abandon/buy-in decisions. If the transfer price is very high, the receiving division might decide not to buy any components from the transferring division because it becomes impossible for it to make a positive contribution. That division might decide to abandon the product line or buy-in cheaper components from outside suppliers.

Motivation. Everyone likes to make a profit and this ambition certainly applies to the divisional managers. If a transfer price was such that one division found it impossible to make a profit, then the employees in that division would probably be demotivated. In contrast, the other division would have an easy ride as it would make profits easily, and it would not be motivated to work more efficiently.

Investment appraisal. New investment should typically be evaluated using a method such as net present value. However, the cash inflows arising from an investment are almost certainly going to be affected by the transfer price, so capital investment decisions can depend on the transfer price.

Taxation and profit remittance. If the divisions are in different countries, the profits earned in each country will depend on transfer prices. This could affect the overall tax burden of the group and could also affect the amount of profits that need to be remitted to head office.

As you can see, therefore, transfer prices can have a profound effect on group performance because they affect divisional performance, motivation and decision making.

The characteristics of a good transfer price

Although not easy to attain simultaneously, a good transfer price should:

Preserve divisional autonomy: almost inevitably, divisionalisation is accompanied by a degree of decentralisation in decision making so that specific managers and teams are put in charge of each division and must run it to the best of their ability. Divisional managers are therefore likely to resent being told by head office which products they should make and sell. Ideally, divisions should be given a simple, understandable objective such as maximising divisional profit.

Be perceived as being fair for the purposes of performance evaluation and investment decisions.

Permit each division to make a profit: profits are motivating and allow divisional performance to be measured using positive ROI or positive RI.

Encourage divisions to make decisions which maximise group profits: the transfer price will achieve this if the decisions which maximise divisional profit also happen to maximise group profit – this is known as goal congruence. Furthermore, all divisions must want to do the same thing. There’s no point in transferring divisions being very keen on transferring out if the next division doesn’t want to transfer in.

Possible transfer prices

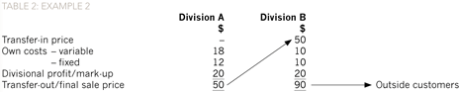

In the following examples, assume that Division A can sell only to Division B, and that Division B’s only source of components is Division A. Example 1 has been reproduced but with costs split between variable and fixed. A somewhat arbitrary transfer price of $50 has been used initially and this allows each division to make a profit of $20.

Example 2

See Table 2. The following rules on transfer prices are necessary to get both parties to trade with one another:

For the transfer-out division, the transfer price must be greater than (or equal to) the marginal cost of production. This allows the transfer-out division to make a contribution (or at least not make a negative one). In Example 2, the transfer price must be no lower than $18. A transfer price of $19, for example, would not be as popular with Division A as would a transfer price of $50, but at least it offers the prospect of contribution, eventual break-even and profit.

For the transfer-in division, the transfer in price plus its own marginal costs must be no greater than the marginal revenue earned from outside sales. This allows that division to make a contribution (or at least not make a negative one). In Example 2, the transfer price must be no higher than $80 as:

$80 (transfer-in price) + $10 (own variable cost) = $90 (marginal revenue)

Usually, this rule is restated to say that the transfer price should be no greater than the net marginal revenue of the receiving division, where the net marginal revenue is marginal revenue less own marginal costs. Here, net marginal revenues = $80 = $90 – $10.

So, a transfer price of $50 (transfer price ≥ $18, ≤ $80), as set above, will work insofar as both parties will find it worth trading at that price.

The economic transfer price rule

The economic transfer price rule is as follows:

Minimum (fixed by transferring division)

Transfer price ≥ marginal cost of transfer‑out division

And

Maximum (fixed by receiving division)

Transfer price ≤ net marginal revenue of transfer‑in division

As well as permitting interdivisional trade to happen at all, this rule will also give the correct economic decision because if the final selling price is too low for the group to make a positive contribution, no operative transfer price is available.

So, in Example 2, if the final selling price were to fall to $25, the group could not make a contribution because $25 is less than the group’s total variable costs of $18 + $10. The transfer price that would make both divisions trade must be no less than $18 (for Division A) but no greater than $15 (net marginal revenue for Division B = $25 – $10), so clearly no workable transfer price is available.

If, however, the final selling price were to fall to $29, the group could make a $1 contribution per unit. A viable transfer price has to be at least $18 (for Division A) and no greater than $19 (net marginal revenue for Division B = $29 – $10). A transfer price of $18.50, say, would work fine.

Therefore, all that head office needs to do is to impose a transfer price within the appropriate range, confident that both divisions will choose to act in a way that maximises group profit. Head office therefore gives each division the impression of making autonomous decisions, but in reality each division has been manipulated into making the choices head office wants.

Note, however, that although we have established the range of transfer prices that would work correctly in terms of economic decision making, there is still plenty of scope for argument, distortion and dissatisfaction. Example 1 suggested a transfer price between $18 and $80, but exactly where the transfer price is set in that range vastly alters the perceived profitability and performance of each sub-unit. The higher the transfer price, the better Division A looks and the worse Division B looks (and vice versa).

In addition, a transfer price range as derived in Example 1 and 2 will often be dynamic. It will keep changing as both variable production costs and final selling prices change, and this can be difficult to manage. In practice, management would often prefer to have a simpler transfer price rule and a more stable transfer price – but this simplicity runs the risk of poorer decisions being made.

Practical approaches to transfer price fixing

In order to address these concerns, some common practical approaches to transfer price fixing exist:

1. Variable cost

A transfer price set equal to the variable cost of the transferring division produces very good economic decisions. If the transfer price is $18, Division B’s marginal costs would be $28 (each unit costs $18 to buy in then incurs another $10 of variable cost). The group’s marginal costs are also $28, so there will be goal congruence between Division B’s wish to maximise its profits and the group maximising its profits. If marginal revenue exceeds marginal costs for Division B, it will also do so for the group.

Although good economic decisions are likely to result, a transfer price equal to marginal cost has certain drawbacks:

Division A will make a loss as its fixed costs cannot be covered. This is demotivating.

Performance measurement is distorted. Division A is condemned to making losses while Division B gets an easy ride as it is not charged enough to cover all costs of manufacture. This effect can also distort investment decisions made in each division. For example, Division B will enjoy inflated cash inflows.

There is little incentive for Division A to be efficient if all marginal costs are covered by the transfer price. Inefficiencies in Division A will be passed up to Division B. Therefore, if marginal cost is going to be used as a transfer price, at least make it standard marginal cost, so that efficiencies and inefficiencies stay within the divisions responsible for them.

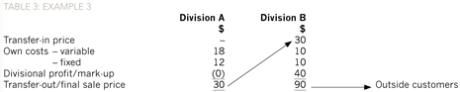

2. Full cost/full cost plus/variable cost plus/market price

Example 3.

See Table 3.

A transfer price set at full cost as shown in Table 3 (or better, full standard cost) is slightly more satisfactory for Division A as it means that it can aim to break even. Its big drawback, however, is that it can lead to dysfunctional decisions because Division B can make decisions that maximise its profits but which will not maximise group profits. For example, if the final market price fell to $35, Division B would not trade because its marginal cost would be $40 (transfer-in price of $30 and own marginal costs of $10). However, from a group perspective, the marginal cost is only $28 ($18 + $10) and a positive contribution would be made even at a selling price of only $35. Head office could, of course, instruct Division B to trade but then divisional autonomy is compromised and Division B managers will resent being instructed to make negative contributions which will impact on their reported performance. Imagine you are Division B’s manager, trying your best to hit profit targets, make wise decisions, and move your division forward by carefully evaluated capital investment.

The full cost plus approach would increase the transfer price by adding a mark up. This would now motivate Division A, as profits can be made there and may also allow profits to be made by Division B. However, again this can lead to dysfunctional decisions as the final selling price falls.

A transfer price set to the market price of the transferred goods (assuming that there is a market for the intermediate product) should give both divisions the opportunity to make profits (if they operate at normal industry efficiencies), but again such a transfer price runs the risk of encouraging dysfunctional decision making as the final selling price falls towards the group marginal cost. However, market price has the important advantage of providing an objective transfer price not based on arbitrary mark ups. Market prices will therefore be perceived as being fair to each division, and will also allow important performance evaluation to be carried out by comparing the performance of each division to outside, stand-alone businesses. More accurate investment decisions will also be made.

The difficulty with full cost, full cost plus, variable cost plus, and market price is that they all result in fixed costs and profits being perceived as marginal costs as goods are transferred to Division B. Division B therefore has the wrong data to enable it to make good economic decisions for the group – even if it wanted to. In fact, once you get away from a transfer price equal to the variable cost in the transferring division, there is always the risk of dysfunctional decisions being made unless an upper limit – equal to the net marginal revenue in the receiving division – is also imposed.

Variations on variable cost

There are two approaches to transfer pricing which try to preserve the economic information inherent in variable costs while permitting the transferring division to make profits, and allowing better performance valuation. However, both methods are somewhat complicated.

Variable cost plus lump sum. In this approach, transfers are made at variable cost. Then, periodically, a transfer is made between the two divisions (Credit Division A, Debit Division B) to account for fixed costs and profit. It is argued that Division B has the correct cumulative variable cost data to make good decisions, yet the lump sum transfers allow the divisions ultimately to be treated fairly with respect to performance measurement. The size of the periodic transfer would be linked to the quantity or value of goods transferred.

Dual pricing. In this approach, Division A transfers out at cost plus a mark up (perhaps market price), and Division B transfers in at variable cost. Therefore, Division A can make a motivating profit, while Division B has good economic data about cumulative group variable costs. Obviously, the divisional current accounts won’t agree, and some period-end adjustments will be needed to reconcile those and to eliminate fictitious interdivisional profits.

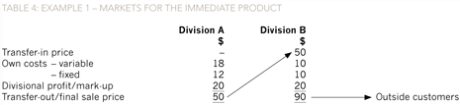

Markets for the intermediate product

Consider Example 1 again, but this time assume that the intermediate product can be sold to, or bought from, a market at a price of either $40 or $60. See Table 4.

(i) Intermediate product bought/sold for $40

Division A would rather transfer to Division B, because receiving $50 is better then receiving $40. Division B would rather buy in at the cheaper $40, but that would be bad for the group because there is now a marginal cost to the group of $40 instead of only $18, the variable cost of production in Division A. The transfer price must, therefore, compete with the external supply price and must be no higher than that. It must also still be no higher than the net marginal revenue of Division B ($90 – $10 = $80) if Division B is to avoid making negative contributions.

(ii) Intermediate product bought/sold for $60

Division B would rather buy from Division A ($50 beats $60), but Division A would sell as much as possible outside at $60 in preference to transferring to Division B at $50. Assuming Division A had limited capacity and all output was sold to the outside market, that would force Division B to buy outside and this is not good for the group as there is then a marginal cost of $60 when obtaining the intermediate product, as opposed to it being made in Division A for $18 only. Therefore, we must encourage Division A to supply to Division B and we can do this by setting a transfer price that is high enough to compensate for the lost contribution that Division A could have made by selling outside. Therefore, Division A has to receive enough to cover the variable cost of production plus the lost contribution caused by not selling outside:

Minimum transfer price = $18 + ($60 – $18) = $60

Basically, the transfer price must be as good as the outside selling price to get Division B to transfer inside the group.

The new rules can therefore be stated as follows:

Economic transfer price rule

Minimum (fixed by transferring division)

Transfer price ≥ marginal cost of transfer-out division + any lost contribution

And

Maximum (fixed by receiving division)

Transfer price ≤ the lower of net marginal revenue of transfer-in division and the external purchase price

Conclusion

You might have thought that transfer prices were matters of little importance: debits in one division, matching credits in another, but with no overall effect on group profitability. Mathematically this might be the case, but only at the most elementary level. Transfer prices are vitally important when motivation, decision making, performance measurement, and investment decisions are taken into account – and these are the factors which so often separate successful from unsuccessful businesses.