There is no doubt that transfer pricing is an area that candidates find difficult. It’s not surprising, then, that when it was examined in June 2014’s Performance Management exam, answers were not always very good.

The purpose of this article is to strip transfer pricing back to the basics and consider, first, why transfer pricing is important; secondly, the general principles that should be applied when setting a transfer price; and thirdly, an approach to tackle exam questions in this area, specifically the question from June 2014’s exam. We will talk about transfer pricing here in terms of two divisions trading with each other. However, don’t forget that these principles apply equally to two companies within the same group trading with each other.

This article assumes that transfer prices will be negotiated between the two parties. It does not look at alternative methods such as dual pricing, for example. This is because, in Performance Management, the primary focus is on working out a sensible transfer price or range of transfer prices, rather than different techniques to setting transfer prices.

Why transfer pricing is important

It is essential to understand that transfer prices are only important in so far as they encourage divisions to trade in a way that maximises profits for the company as a whole. The fact is that the effects of inter-divisional trading are wiped out on consolidation anyway. Hence, all that really matters is the total value of external sales compared to the total costs of the company. So, while getting transfer prices right is important, the actual transfer price itself doesn’t matter since the selling division’s sales (a credit in the company accounts) will be cancelled out by the buying division’s purchases (a debit in the company accounts) and both figures will disappear altogether. All that will be left will be the profit, which is merely the external selling price less any cost incurred by both divisions in producing the goods, irrespective of which division they were incurred in.

As well as transfer prices needing to be set at a level that maximises company profits, they also need to be set in a way that is compliant with tax laws, allows for performance evaluation of both divisions and staff/managers, and is fair and therefore motivational. A little more detail is given on each of these points below:

- If your company is based in more than one country and it has divisions in different countries that are trading with each other, the price that one division charges the other will affect the profit that each of those divisions makes. In turn, given that tax is based on profits, a division will pay more or less tax depending on the transfer prices that have been set. While you don’t need to worry about the detail of this for the Performance Management exam, it’s such an important point that it’s simply impossible not to mention it when discussing why transfer pricing is important.

- From bullet point 1, you can see that the transfer price set affects the profit that a division makes. In turn, the profit that a division makes is often a key figure used when assessing the performance of a division. This will certainly be the case if return on investment (ROI) or residual income (RI) is used to measure performance. Consequently, a division may, for example, be told by head office that it has to buy components from another division, even though that division charges a higher price than an external company. This will lead to lower profits and make the buying division’s performance look poorer than it would otherwise be. The selling division, on the other hand, will appear to be performing better. This may lead to poor decisions being made by the company.

- If this is the case, the manager and staff of that division are going to become unhappy. Often, their pay will be linked to the performance of the division. If divisional performance is poor because of something that the manager and staff cannot control, and they are consequently paid a smaller bonus for example, they are going to become frustrated and lack the motivation required to do the job well. This will then have a knock-on effect to the real performance of the division. As well as being seen not to do well because of the impact of high transfer prices on ROI and RI, the division really will perform less well.

The impact of transfer prices could be considered further but these points are sufficient for the level of understanding needed for the Performance Management exam. Let us now go on to consider the general principles that you should understand about transfer pricing. Again, more detail could be given here and these are, to some extent, oversimplified. However, this level of detail is sufficient for the Performance Management exam.

General principles about transfer pricing

1. Where there is an external market for the product being transferred

Minimum transfer price

When we consider the minimum transfer price, we look at transfer pricing from the point of view of the selling division. The question we ask is: what is the minimum selling price that the selling division would be prepared to sell for? This will not necessarily be the same as the price that the selling division would be happy to sell for, although, as you will see, if it does not have spare capacity, it is the same.

The minimum transfer price that should ever be set if the selling division is to be happy is: marginal cost + opportunity cost.

Opportunity cost is defined as the ‘value of the best alternative that is foregone when a particular course of action is undertaken’. Given that there will only be an opportunity cost if the seller does not have any spare capacity, the first question to ask is therefore: does the seller have spare capacity?

Spare capacity

If there is spare capacity, then, for any sales that are made by using that spare capacity, the opportunity cost is zero. This is because workers and machines are not fully utilised. So, where a selling division has spare capacity the minimum transfer price is effectively just marginal cost. However, this minimum transfer price is probably not going to be one that will make the managers happy as they will want to earn additional profits. So, you would expect them to try and negotiate a higher price that incorporates an element of profit.

No spare capacity

If the seller doesn’t have any spare capacity, or it doesn’t have enough spare capacity to meet all external demand and internal demand, then the next question to consider is: how can the opportunity cost be calculated? Given that opportunity cost represents contribution foregone, it will be the amount required in order to put the selling division in the same position as they would have been in had they sold outside of the group. Rather than specifically working an ‘opportunity cost’ figure out, it’s easier just to stand back and take a logical approach rather than a rule-based one.

Logically, the buying division must be charged the same price as the external buyer would pay, less any reduction for cost savings that result from supplying internally. These reductions might reflect, for example, packaging and delivery costs that are not incurred if the product is supplied internally to another division. It is not really necessary to start breaking the transfer price down into marginal cost and opportunity cost in this situation.

It’s sufficient merely to establish:

(i) what price the product could have been sold for outside the group

(ii) establish any cost savings, and

(iii) deduct (ii) from (i) to arrive at the minimum transfer price.

At this point, we could start distinguishing between perfect and imperfect markets, but this is not necessary in Performance Management. There will be enough information given in a question for you to work out what the external price is without focusing on the market structure.

We have assumed here that production constraints will result in fewer sales of the same product to external customers. This may not be the case; perhaps, instead, production would have to be moved away from producing a different product. If this is the case the opportunity cost, being the contribution foregone, is simply the shadow price of the scarce resource.

In situations where there is no spare capacity, the minimum transfer price is such that the selling division would make just as much profit from selling internally as selling externally. Therefore, it reflects the price that they would actually be happy to sell at. They shouldn’t expect to make higher profits on internal sales than on external sales.

Maximum transfer price

When we consider the maximum transfer price, we are looking at transfer pricing from the point of view of the buying division. The question we are asking is: what is the maximum price that the buying division would be prepared to pay for the product? The answer to this question is very simple and the maximum price will be one that the buying division is also happy to pay.

The maximum price that the buying division will want to pay is the market price for the product – ie whatever they would have to pay an external supplier for it. If this is the same as the selling division sells the product externally for, the buyer might reasonably expect a reduction to reflect costs saved by trading internally. This would be negotiated by the divisions and is called an adjusted market price.

2. Where there is no external market for the product being transferred

Sometimes, there will be no external market at all for the product being supplied by the selling division; perhaps it is a particular type of component being made for a specific company product. In this situation, it is not really appropriate to adopt the approach above. In reality, in such a situation, the selling division may well just be a cost centre, with its performance being judged on the basis of cost variances. This is because the division cannot really be judged on its commercial performance, so it doesn’t make much sense to make it a profit centre. Options here are to use a cost based approach to transfer pricing but these also have their advantages and disadvantages.

Cost based approaches

Variable cost

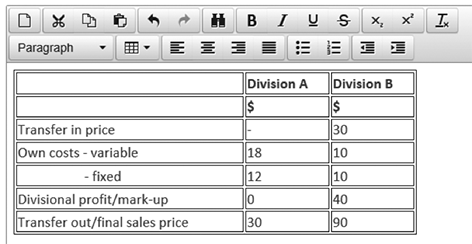

A transfer price set equal to the variable cost of the transferring division produces very good economic decisions. If the transfer price is $18, Division B’s marginal costs would be $28 (each unit costs $18 to buy in then incurs another $10 of variable cost). The group’s marginal costs are also $28, so there will be goal congruence between Division B’s wish to maximise its profits and the group maximising its profits. If marginal revenue exceeds marginal costs for Division B, it will also do so for the group.

Although good economic decisions are likely to result, a transfer price equal to marginal cost has certain drawbacks:

Division A will make a loss as its fixed costs cannot be covered. This is demotivating.

Performance measurement is also distorted. Division A is condemned to making losses while Division B gets an easy ride as it is not charged enough to cover all costs of manufacture. This effect can also distort investment decisions made in each division. For example, Division B will enjoy inflated cash inflows.

There is little incentive for Division A to be efficient if all marginal costs are covered by the transfer price. Inefficiencies in Division A will be passed up to Division B. Therefore, if marginal cost is going to be used as a transfer price, it at least should be standard marginal cost, so that efficiencies and inefficiencies stay within the divisions responsible for them.

Full cost/Full cost plus/Variable cost plus

A transfer price set at full cost or better, full standard cost is slightly more satisfactory for Division A as it means that it can aim to break even. Its big drawback, however, is that it can lead to dysfunctional decisions because Division B can make decisions that maximise its profits but which will not maximise group profits. For example, if the final market price fell to $35, Division B would not trade because its marginal cost would be $40 (transfer-in price of $30 plus own marginal costs of $10). However, from a group perspective, the marginal cost is only $28 ($18 + $10) and a positive contribution would be made even at a selling price of only $35. Head office could, of course, instruct Division B to trade but then divisional autonomy is compromised and Division B managers will resent being instructed to make negative contributions which will impact on their reported performance. Imagine you are Division B’s manager, trying your best to hit profit targets, make wise decisions, and move your division forward by carefully evaluated capital investment.

The full cost plus approach would increase the transfer price by adding a mark-up. This would now motivate Division A, as profits can be made there and may also allow profits to be made by Division B. However, again this can lead to dysfunctional decisions as the final selling price falls.

The difficulty with full cost, full cost plus and variable cost plus is that they all result in fixed costs and profits being perceived as marginal costs as goods are transferred to Division B. Division B therefore has the wrong data to enable it to make good economic decisions for the group – even if it wanted to. In fact, once you get away from a transfer price equal to the variable cost in the transferring division, there is always the risk of dysfunctional decisions being made unless an upper limit – equal to the net marginal revenue in the receiving division – is also imposed.

Tackling a transfer pricing question

Thus far, we have only talked in terms of principles and, while it is important to understand these, it is equally as important to be able to apply them. The following question came up in June 2014’s exam. It was actually a 20-mark question with the first 10 marks in part (a) examining divisional performance measurement and the second 10 marks in part (b) examining transfer pricing. Parts of the question that were only relevant to part (a) have been omitted here however the full question can be found on ACCA’s website. The question read as follows:

Reproduction of exam question

Relevant extracts from part (a)

The Rotech group comprises two companies, W Co and C Co.

W Co is a trading company with two divisions: the design division, which designs wind turbines and supplies the designs to customers under licences and the Gearbox division, which manufactures gearboxes for the car industry.

C Co manufactures components for gearboxes. It sells the components globally and also supplies W Co with components for its Gearbox manufacturing division.

The financial results for the two companies for the year ended 31 May 2014 are as follows:

(b) C Co is currently working to full capacity. The Rotech group’s policy is that group companies and divisions must always make internal sales first before selling outside of the group. Similarly, purchases must be made from within the group wherever possible. However, the group divisions and companies are allowed to negotiate their own transfer prices without interference from head office.

C Co has always charged the same price to the Gearbox division as it does to its external customers. However, after being offered a 5% lower price for the similar components from an external supplier, the manager of the Gearbox division feels strongly that the transfer price is too high and should be reduced. C Co currently satisfies 60% of the external demand for its components. Its variable costs represent 40% of the total revenue for the internal sales of the components.

Required:

Advise, using suitable calculations, the total transfer price or prices at which the components should be supplied to the Gearbox division from C Co.

(10 marks)

Approach

- As always, you should begin by reading the requirement. In this case, it is very specific as it asks you to ‘advise, using suitable calculations…’ In a question like this, it would actually be impossible to ‘advise’ without using calculations anyway and your answer would score very few marks. However, this wording has been added in to provide assistance. In transfer pricing questions, you will sometimes be asked to calculate a transfer price/range of transfer prices for one unit of a product. However, in this case, you are being asked to calculate the total transfer price for the internal sales. You don’t have enough information to work out a price per unit.

- Allocate your time. Given that this is a 10-mark question then, since it is a three-hour exam, the total time that should be spent on this question is 18 minutes.

- Work through the scenario, highlighting or underlining key points as you go through. When tackling part (a) you would already have noted that C Co makes $7.55m of sales to the Gearbox Division (and you should have noted who the buying division was and who the selling division was). Then, in part (b), the first sentence tells you that C Co is currently working to full capacity. Highlight this; it’s a key point, as you should be able to tell now. Next, you are told that the two divisions must trade with each other before trading outside the group. Again, this is a key point as it tells you that, unless the company is considering changing this policy, C Co is going to meet all of the Gearbox division’s needs.

Next, you are told that the divisions can negotiate their own transfer prices, so you know that the price(s) you should suggest will be based purely on negotiation.

Finally, you are given information to help you to work out maximum and minimum transfer prices. You are told that the Gearbox division can buy the components from an external supplier for 5% cheaper than C Co sells them for. Therefore, you can work out the maximum price that the division will want to pay for the components. Then, you are given information about the marginal cost of making gearboxes, the level of external demand for them and the price they can be sold for to external customers. You have to work all of these figures out but the calculations are quite basic. These figures will enable you to calculate the minimum prices that C Co will want to sell its gearboxes for; there are two separate prices as, when you work the figures through, it becomes clear that, if C Co sold purely to the external market, it would still have some spare capacity to sell to the Gearbox division. So, the opportunity cost for some of the sales is zero, but not for the other portion of them. - Having actively read through the scenario, you are now ready to begin writing your answer. You should work through in a logical order. Consider the transfer from both C Co’s perspective (the minimum transfer price), then Gearbox division’s perspective (the maximum transfer price), although it doesn’t matter which one you deal with first. Head up your paragraphs so that your answer does not simply become a sea of words. Also, by heading up each one separately, it helps you to remain focused on fully discussing that perspective first. Finally, consider the overall position, which in this case is to suggest a sensible range of transfer prices for the sale. There is no single definitive answer but, as is often the case, a range of prices that would be acceptable.

The suggested solution is shown below.

Always remember that you should only show calculations that actually have some relevance to the answer. In this exam, many candidates actually worked out figures that were of no relevance to anything. Such calculations did not score marks.

Reproduction of answer

From C Co’s perspective:

C Co transfers components to the Gearbox division at the same price as it sells components to the external market. However, if C Co were not making internal sales then, given that it already satisfies 60% of external demand, it would not be able to sell all of its current production to the external market. External sales are $8,010,000, therefore unsatisfied external demand is ([$8,010,000/0.6] – $8,010,000) = $5,340,000.

From C Co’s perspective, of the current internal sales of $7,550,000, $5,340,000 could be sold externally if they were not sold to the Gearbox division. Therefore, in order for C Co not to be any worse off from selling internally, these sales should be made at the current price of $5,340,000, less any reduction in costs that C Co saves from not having to sell outside the group (perhaps lower administrative and distribution costs).

As regards the remaining internal sales of $2,210,000 ($7,550,000 – $5,340,000), C Co effectively has spare capacity to meet these sales. Therefore, the minimum transfer price should be the marginal cost of producing these goods. Given that variable costs represent 40% of revenue, this means that the marginal cost for these sales is $884,000. This is, therefore, the minimum price which C Co should charge for these sales.

In total, therefore, C Co will want to charge at least $6,224,000 for its sales to the Gearbox division.

From the Gearbox division’s perspective:

The Gearbox division will not want to pay more for the components than it could purchase them for externally. Given that it can purchase them all for 95% of the current price, this means a maximum purchase price of $7,172,500.

Overall:

Taking into account all of the above, the transfer price for the sales should be somewhere between $6,224,000 and $7,172,500.

Summary

The level of detail given in this article reflects the level of knowledge required for Performance Management as regards transfer pricing questions of this nature. It’s important to understand why transfer pricing both does and doesn’t matter and it is important to be able to work out a reasonable transfer price/range of transfer prices.

The thing to remember is that transfer pricing is actually mostly about common sense. You don’t really need to learn any of the specific principles if you understand what it is trying to achieve: the trading of divisions with each other for the benefit of the company as a whole. If the scenario in a question was different, you may have to consider how transfer prices should be set to optimise the profits of the group overall. Here, it was not an issue as group policy was that the two divisions had to trade with each other, so whether this was actually the best thing for the company was not called into question. In some questions, however it could be, so bear in mind that this would be a slightly different requirement. Always read the requirement carefully to see exactly what you are being asked to do.